ON FRIDAY Australia’s federal Parliament delivered landmark modern slavery legislation, which requires big businesses to act on slavery in their operations and supply chains.

I was walking to the Collingwood Post Office as the Act was passed. En route, my eye was caught by a flyer posted on a footbridge (pictured) suggesting Australians are made ‘slaves’ by having to vote. Voting, it insinuated, is a pointless excercise in revolving disempowerment where one ‘master’ is simply exchanged for another.

These coinciding actions brought me to reflect on our understandings and responses to slavery, now that we are significantly tightening our legal obligations to act on it.

Firstly, to the real thing. Slavery is the ultimate abuse of power relations where indiviuals, groups and entire systems deceive, coerce and violently treat people to deprive them of their freedom to choose how they live, work and simply be.

The Modern Slavery Act requires large businesses with over $AUD100 million annual turnover to act on slavery in their own operations and supply chains, by describing:

- their structure, operations and supply chains

- the potential risk of modern slavery in their operations and supply chains

- actions they’ve taken to assess and address those risks, including due diligence and remediation processes; and

- how they assess the effectiveness of those actions.

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), whether exporters, those sourcing key inputs from overseas, or those with migrant workers are also going to be affected by the flow-on effects of these reporting requirements. SMEs face the real risk of reputational and financial loss if they don’t act themselves.

The ‘slavery’ described in the flyer refes to the genuine disconnect between voters and our governments. It invokes our legitimate anger and frustration when our votes don’t translate to the outcomes we seek as individuals and communities. But the very real abuses of power and power relations that go on in our democratic system are not an excercise in enslaving the voting public. This flyer trivialised and obscured the reality of slavery.

Slavery went on just one kilometre away from Parliament House where the Modern Slavery Bill was being debated.

This system that we’re goaded into despising, even opting out of when the going gets tough, is the system that delivers the policy and structural settings we need to tackle the slavery in our midst. It was our votes that delivered two Australian governments (federal and NSW) that have made these laws possible.

Slavery is a pernicious distortion of power relations that doesn’t just happen ‘somewhere else’. It thrives ‘hidden in plain sight’ in our homes, businesses and neighbourhoods.

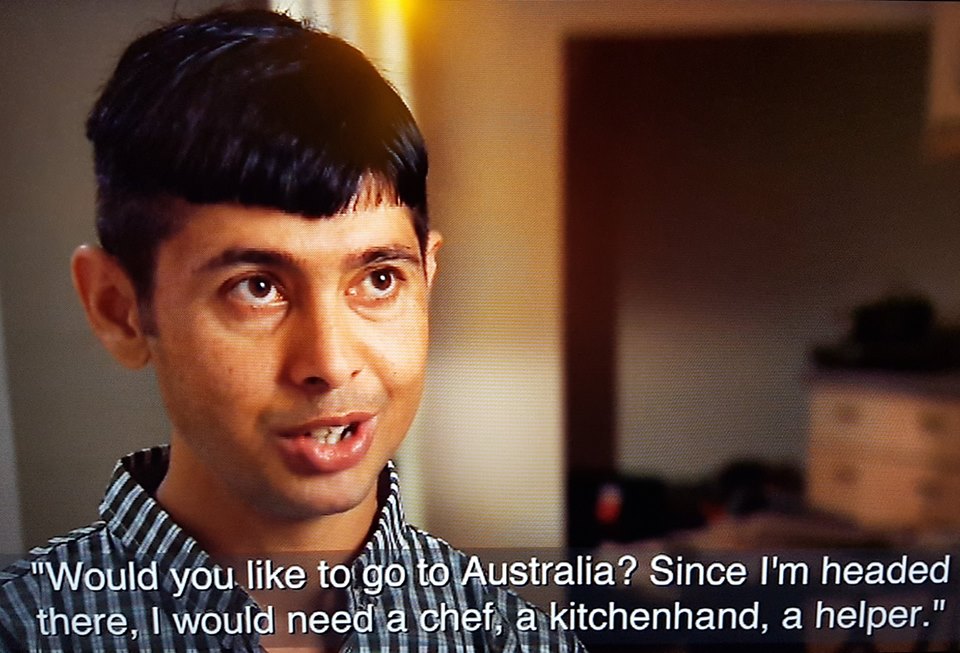

Slavery went on just one kilometre away from Parliament House where the Modern Slavery Bill was being debated. Here, prosecution-immune diplomats trafficked men and women from their home country with the promise of the opportunity of a lifetime. They promptly enslaved them in domestic servitude. Slavery doesn’t get much more in-your-face than that.

Shahid Mahmood, chauffeur of to-be-Pakistani High Commissioner Naela Chohan. She trafficked Shahid to Australia with the promise of a work pathway, then took away his passport and enslaved him. (Image: InterMondo, from ABC ‘Four Corners’)

Modern slavery is also a well-established form of business management practice in which networks of trust and shared identity are exploited to recruit, traffic and enslave people. Our values systems, expectations and behaviours as consumers help slavery to flourish.

Here in Australia, young international graduates with work rights, desperate to get a toehold in their profession and fufill their families’ investment in them, can be inveigled, through networks of shared cultural identity and kinship, into exploitation, even enslavement. They are kept there with threats of handing them over to law enforcement agencies, forfeiting their visa and reprisals for their families.

Other work visa holders are similarly recruited, trafficked and deployed in conditions of slavery at their destination workplace. The trafficking does not have to be international. It happens within Australia, even within the same city.

Graduates desperate to get a toehold in their profession can be tricked, through networks of shared cultural identity and kinship, into exploitation, even enslavement. (Image Pexels Ruslan/Burlaka)

Sophisticated – and simple – techniques are used to deflect attention from the fact that these actions are illegal.

Slavery happens in businesses, large and small, in traditionally high and low risk sectors. Enslavers stay well ahead of the law and our own confused understandings of what slavery really means in our communities and businesses.

Slavery is lucrative, yet bad for business. It under-prices and undermines legitimate businesses. Slavery erodes the essential elements businesses need to survive and be healthy: empowered individuals, healthy, safe communities, healthy environment, good governance and legal protection.

Businesses that turn a blind eye to slavery in their systems, or businesses that exploit workers as part of their business model or as a response to financial pressures, risk reputational damage, legal consequences, financial loss and even business failure.

I don’t agree with everything about the Modern Slavery Act. A few key points here.

Like many other groups (and as recognised in the NSW Modern Slavery Act), I believe reporting requirements should start with businesses with over $50 million, rather than $100 million, annual turnover. Focusing on large corporates because of their ability to exert the greatest influence on slavery outcomes in their systems is partly flawed reasoning. It overlooks the multiple ways in which influence is exerted and how slavery can and should be addressed.

‘It takes a village’ to tackle slavery. That village includes smaller businesses, which intersect intimately with local communities where slavery flourishes but which may also conceal slavery in their own systems. I’m batting for the village.

For all those other entities across our business ecosystem that are part of the problem and the solution on slavery – well, they’ve been overlooked.

I have argued consistently that SMEs must be at the table on modern slavery. Yet Australia’s largest employer sector and major supplier to corporates has received little or poorly targeted attention.

Nottingham City’s goal to become the UK’s first slavery-free city powerfully illustrates that ‘it takes a village’ to tackle slavery. That village includes SMEs, which can and do intersect intimately with local communities where slavery quietly flourishes. And which may also conceal slavery in their own systems.

Nottingham, led by Nottingham University’s Right’s Lab, is harnessing SMEs and local communities to act powerfully by acting locally on slavery.

Instead of a Modern Slavery Commissioner to help implement the Act and help businesses understand slavery and how to act, a business unit is being established to carry out this work. I agree with the function of a unit but not the absence of a Commissioner.

Paradoxically, the late decision to give the Home Affairs Minister discretionary powers to enforce compliance also contradicts the ‘race to the top’ spirit envoked in the crafting of the legislation.

In contrast, the NSW Act had the foresight to follow the UK Modern Slavery Act by legislating for an independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner to oversee – and, importantly, humanise – these activities. It also introduces a scale of penalties, removing the need to add yet more ministerial interventions to a massive waiting list for other ministerial interventions.

Former UK Commissioner Kevin Hyland was and remains in the UK a powerful unifying force for acting on slavery, as opposed to the facelessness of a unit. I would argue that a highly respected appointee would be a powerful nucleus for businesses under the $100 million threshold that want to act on slavery.

There is an expectation that SME partners of corporates with anti-slavery reporting requirements will ‘police’ their own supply chains and do the heavy lifting on addressing slavery, even though it’s acknowledged SMEs will struggle to do this with their resources and without the leverage over suppliers enjoyed by corporates.

So, there are weaknesses, gaps and flawed assumptions inherent in the legislation.

But most importantly, the Act has landed.

The Modern Slavery Act is a multipartisan effort, built on the voluntary efforts of prominent and little-known groups. All, despite their own agendas, have worked through their differences. They haven’t turned away, as this flyer implies we should do when our voices, like the genuinely enslaved, are disregarded.

As a microbusiness, I have lent a small voice to a legislative process forged by powerful voices and interests. These voices and interests influence our understanding of modern slavery and shape our response to it.

In a complementary spirit, I’ve pinned InterMondo’s colours to the mast of SMEs. I’m focussing on supporting SMEs to tackle slavery and hold them accountable too.

I’m batting for the village.

As part of this, I’m reaching out to my networks to complete a brief Typeform survey for research I’m conducting on how SMEs are responding to worker exploitation in their systems. The answers will help me develop guidance specifically for SMEs, helping them act on slavery. It will also document their activities for business partners, investors and customers that demand evidence of what they’re doing.

If your business is acting/wants to act to prevent worker exploitation in your supply chains, I want to hear from you!

The survey is confidential and I will share general findings through social media and email.

Tonight’s a night for a toast to our Federal Parliament and messy, yet functioning, democracy that’s delivered this legislation. Tomorrow – on with the job.

Anna Ridgway, Director of InterMondo, helps people & business adjust how they communicate across cultures to better manage their business relationships, including dismantling slavery.