This is the story of a professional dream gone bad overseas in a country with a known yet poorly understood cultural environment. It has parallels with the stories of countless professionals gifted with expertise, experience and cultural knowledge but lack of cultural flexibility in their behaviours, who come unstuck when seeking to establish themselves professionally and socially outside their home environment.

Our subject, Thibault*, is a multilingual French Polynesian of mixed European heritage and part of an ethnically Caucasian cultural and economic elite. Thibault is also a post doctorate specialist on Australian literature. His educational credentials, professional accomplishments and international accolades – highly prized cultural attributes – have provided him opportunities to climb the academic ladder. Although he may not be aware of it or choose to admit it, there’s little doubt that in the social hierarchies that prevail across French Polynesia, Thibault’s socio-economic status would also have provided opportunities not available to many others. But Thibault asserts that his merits alone are behind his success. Meritocracy, for him, is real and works.

When our story opens, Thibault is ready to dramatically expand his professional horizons. His dream is to work and eventually settle permanently in Australia, where his now-ailing grandparents migrated from Europe after the Second World War. Thibault is confident that, with his deep knowledge of Australia, he’s well prepared to make the big leap.

So in 2012, Thibault takes a sabbatical and comes to Australia. He’s lined up a teaching post and intends to travel a little before settling into an educational position, either as an academic or teacher. His expectations are high.

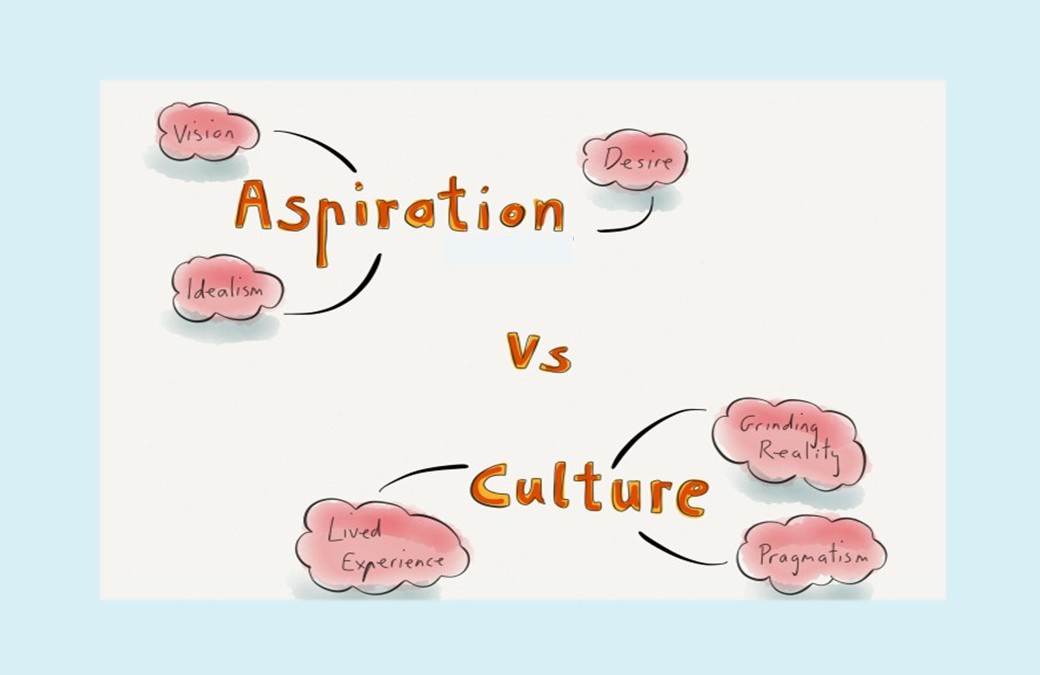

After the first ‘euphoric’ months of novelty and discovery, the reality of Australian culture and the constraints of Australia’s employment market start to set in. Thibault’s frustrations emerge. Things are not as he thought they would be; and his bewilderment is compounded by his failure to find the professional role he believes is his due.

Thibault is unprepared for falling into the ranks of highly credentialled, experienced professionals in Australia and globally who are struggling in today’s tumultuous employment market of position unavailability and insecurity. He has had no experience of this world of casual, sessional work with no guarantee of ongoing employment. As he sees it, in Australia it’s all about who you know and petty job protectionism, with merit and credentials routinely ignored. While straining after the ever-receding Australia dream, he shares with friends and colleague his opinion that it’s these negative Australian shortcomings which are behind his predicament. This sharing risks antagonising local well-wishers whose support he seeks.

Thibault’s confusion, personal family loss and sense of deep offense are writ large in this group email he sends to friends and colleagues around Australia in a final plea for a secure position that would allow him to stay:

Dearest Friends,

I have not suspected that I would have to write this kind of email one day. As things stand at present, I must return to French Polynesia by early February 2014 to resume my life-tenured job over there.

I thought that by coming over to Australia with a fine pedigree (academic accolades, highest qualifications with distinctions, commended books and editorial ventures, literary awards and successful grants) and several hats ( teacher of ESL, French and Latin; writer, translator, critic, editor, reviewer, essayist, publisher, etc.), I would be able to land a contract or an ongoing position in a nice work environment. Instead, I have been made casual, without the prospect of growing a career in Australia, and I have met a series of job-protective setbacks that have added distress to the loss of my grandparents.

Coming from a meritocratic background where efforts are automatically rewarded with positive results, I have not suspected I would have to beg my friends and connections to circulate my resume so that some deus ex machina would enable me to stay in Australia and earn a decent living while looking after my grandma who has been placed in an aged care institution. Failing this, she will remain isolated in a nursing home without the benefit of any family visit for the rest of her life.

I have a reprieve of 2 weeks or so to land a full-time, if not 0.5-0.8, job. I have two weeks to secure an income that would enable me to establish myself in Australia. So I appeal to your generosity to use your networks and circulate this appeal to decision makers and recruiters you might know.

Heartfelt thanks.

Kindest regards,

Thibault.

The appeal of frustration, anger, impending personal loss and self-pity do not win Thibault his eleventh-hour reprieve. I was a recipient of this and an earlier email appeal but was in no position to take up his case. In reality – my sympathy tempered by hostile astonishment at the tenor his complaints – I felt no desire to do so, either.

There is a high rate of expatriate failure, stemming most significantly from failure to adjust culturally

Thibault returns to French Polynesia to pick up where he left off. Meanwhile, he has experienced the highs and lows of expat life as an expat in Australia. His work, friendships and academic networks have afforded him deep experience into daily Australian life and in the nuances of Australian culture. He has also experienced the unaccustomed, personal and professional humiliation of uninterest and failure. On his return, he has to work through the psychological challenges of reverse culture shock and a readjustment to the local environment.

I was introduced to Thibault early in his stay and, over the course of social events, group emails and social media postings, observed the unfolding of his situation. We shared a number of long, impassioned debates, walking from bar to bar across city evening streets and over beer and tapas as friends arrived and left.

I enjoyed the intellectual cut and thrust, but secretly felt confronted by his conversational style and his ill-concealed resentment. I longed to ask why he wasn’t grateful to have had the means and opportunity to live, work and travel in Australia for the time he was here. And I itched to remind him that Australia owed him nothing. Back home, I would read and reread about the cultural values and codes that underpin the way French people debate and discuss issues, so different from my own. I searched the internet for insights on French Polynesian post-colonial culture. I was not him but I tried to understand his unresolved frustrations.

To me, Thibault’s dilemma was a powerful and personal lesson of the importance of deep cultural preparation for relocating internationally, even to a place for which you have deep knowledge and even expert knowledge. No less important is being prepared to work through the confronting psychological challenges of adjusting your attitudes and behaviours in a new cultural environment, without losing a sense of your own self. Humility here is a fundamental atttribute – the ability to be open to learning and being prepared to change one’s behaviours. And ultimately, of being prepared to make mistake after cultural mistake but not to become embittered or calcified by adverse outcomes – rather, to learn from them and apply them to different cultural experiences.

Thibault did not seem able to show or appreciate these attributes in his deeply confronting situation. I could not see any openness to working through this personal disruption towards adjusting his behaviours. Sadly, Thibault had to contend also with the death of one of his grandparents and the moving of the other into an aged-care facility – in isolation from the remainder of the family. The sands also ran out on Thibault’s last opportunity to be close to his remaining grandparent.

Would this have made a difference? Would it have led to the critical full-time position? It’s impossible to know but I believe that Thibault’s lack of cultural preparedness and the unconscious cultural values and behaviours underpinning his communication style in his search for a permanent post would have served him poorly.

Thibault was no more nor less entitled than any other person with talent and drive to ‘make it’ in another country. His lack of cultural flexibility is common to many other such people with talent and drive, whether posted internationally, seeking to expand their business in new markets or spearheading an initiative internationally. Or simply taking a calculated chance of living and working abroad.

In Thibault’s case, only he can decide whether his own international relocation experience was ultimately a success or failure. Yes, his particular dream of work and life in Australia was torpedoed. I hope that with time and perspective, his insights from this experience will enrich his life and hopefully deepen his appreciation of and future literary contributions to Australian culture.

*For privacy, names and some details have been changed.

Anna Ridgway, Director at InterMondo, helps people overcome their own deeply-held cultural resistances and fear of making mistakes in different cultural settings to adjust their behaviours and pursue their business objectives without ‘losing themselves’. You can contact Anna at anna@intermondo.com.au to find out more.