At a Christmas barbecue last year, I got chatting with our host’s 15-year old daughter (let’s call her Madison) about the school she and I both attended, a large Melbourne private college.

As we compared then-and-now notes, Madison said, ‘You know what they keep doing and I wish they wouldn’t?’

What’s that?’ I said.

‘They keep getting in all these guest speakers that are always ex students and they’re always incredibly successful people. I just wish they’d get some other people in or at least get an ex-student who wasn’t successful for a change.’

Wow – strong words and unexpected. It later got me thinking. Why would this happy, confident, privileged young woman with a bright future ahead of her be yearning to find out about the darker side of adulthood – the struggles and the failures, not the achievements?

Had she taken a look through a glass darkly to an uncertain world, turned back to her protective educational guardians and thought: ‘Don’t bullshit me’?

In recent times I’ve been reflecting on my own years of learning and moral growth and how I unthinkingly assumed that, as the fortunate product of my home and community environment, endowed with intelligence and fervour, I would take my assigned place in the world of work, marriage, children, home ownership and tonnes of travel. ‘You’re capable of anything. You can be anything you choose to be – go out and take your place in the world’ we were told.

And so I did. But the trajectory of my life and career, like that of so many others, has been a slow-burn realisation of how poorly my education equipped me to negotiate my way through a world of deep, structural inequality. I’ve had to learn it all through painful experience and drawing on a strong moral core. And this is as a ‘lucky’ white Caucasian, blessed to be born and live in Australia.

Throughout my twenties and into my thirties I kept my head down as I barrelled through studies, a shifting employment market, relationships and relationship breakdown, figuring out my career path.

The penny only started to drop after I wrenched myself out of Australia following my marriage breakdown. I’d endured demoralising years attempting to rise out of casualised positions in bookselling, admin work and contract editing and break into a role in the publishing industry worthy of my talent, passion and education (Follow your dreams, girls!).

Since I wasn’t prepared to murder an editor and assume their identity, I followed instead another lifetime goal to work in El Salvador.

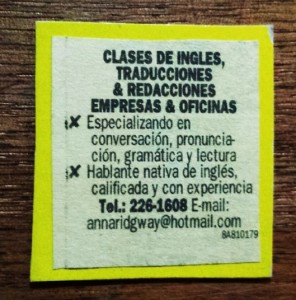

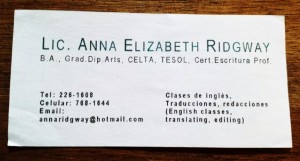

My business card in El Salvador, with qualifications and title carefully translated and adjusted to meet business expectations

The first shock wasn’t just a gender shock but a profound cultural one too that impacted my financial security and my moral universe.

As a project coordinator in El Salvador, my salary was inadequate to support my needs in a setting where I had no family or sufficiently strong social network to support me. My US-born, Salvadoran-based employer would periodically ignore my contract by siphoning off the small supplementary income I was entitled to by doing interpreting and translating on their behalf. Organisations I did this work for would also keep their hand on their wallet on the grounds that I wasn’t Salvadoran.

I didn’t know how to seek redress for myself and the shock of blatant corruption left me in a state of dazed retreat, stammering ineffectually ‘Ésto no es lo dice mi contrato – ¡no me parece justo!’ (My contract doesn’t say this – it doesn’t seem fair). All my years of language study, knowledge of El Salvador and even my earlier marriage to a Salvadoran hadn’t prepared me for this.

What could I do? I sucked it up, of course.

I then sought business as an independent contractor. I studied the classified sections of the two main Salvadoran dailies, La Prensa Gráfica and El Diario de Hoy, and placed a carefully worded advertisement.

I started to receive phone calls from men who were delighted to chat and eventually to meet – not in a client-service provider sense, you understand. I learnt to recognise these calls and close down the conversations. Reluctantly, I eventually abandoned this avenue. My social connections were still too tenuous to open doors. I’d hit a wall.

I was saved by reconnecting with earlier editing clients and teaching business English to company executives.

But how ill prepared I was for the shock of being sexually preyed upon and of blatant corruption. And how unprepared for doing business in an unfamiliar environment. I wryly thought how my school peers one secretly looked down on for taking the ‘business school’ stream were streets ahead of me.

Back in Australia and over the next decade, I put my head down again to grow my career and keep my own business pedalling along on the side.

This was at times a fraught business. I had resolutely ignored the signs of the bias – overt and unconscious – and noxious turf protection on both sides of the gender divide that characterise our professional world. How could I admit to it?

Instead, I admired my own tenacity and skill. I was the person that could charmingly fend off machista males in Spanish. I was the person that got on well with my male peers and leaders. I was the person that led initiatives, networked par excellence, upheld the reputation of my organisation in a hostile environment. I’d earned my seat at the table, even as those peers and leaders passed me over at drinks, left me out of meetings and email communication loops, sidelined me at professional events. It was wired into my DNA that with drive and ambition anyone could be what they wanted to be.

That’s where Madison’s comment struck me.

If as a young person you have no insight and no preparation for structural bias or outright discrimination, no tools to equip you to deal with sexually predatory treatment, how can you negotiate your way through it? In the end, you’re left psychologically reeling, punch drunk. You have no David skills to bring down the Goliath behemoth and prevail. Either you battle through, girding your loins for the psychological – and probably financial – consequences, or your endure, feeling that your options are limited or non-existent.

I’ve witnessed the latter with bright, capable women who may have children, may have an unemployed spouse, may be grimly trying to forge a career, may have endured domestic violence, may have a mortgage, who cower down and just endure the rusted-on discrimination and workplace bullying because they’re afraid to deal with the change, the uncertainty of the job market.

Better the devil who’s jumped on your unprotected back…

My neighbours recently told me about a friend who’d embarked upon a relationship that was fast degenerating into domestic violence. They were bewildered. How could she let her self get into this? She was a gusty feminist, an intelligent, vibrant woman. She’d always said: ‘If anyone ever started treating me like this, I’d walk out’. Yet here she was, shrinking into a fearful, cowed doormat, finding reasons to stay, not get the hell out. I got it. This woman’s ‘strength’ was entirely theoretical. She’d had no preparation for the shock of the reality, no psychological tools at hand. Another demoralising example of why so many supposedly strong women end up as domestic violence victims.

I also believe that there’s a parallel with structural bias in business, why in a country like Australia our success in transforming inequality in the workplace is so depressingly incremental. Women and other cultural groups who are subject to discrimination are ill-equipped for the experience. When the penny drops in their consciousness, it’s often too late and they are professionally and socially isolated in their struggle.

Miette, the gusty protagonist from Jeunet & Caro ‘The City of Lost Children. Scratching out a precarious passage through a hostile adult environment.

Now settling into growing my consulting business, building my brand and clientele, I’ve been reaching into the export community. At a recent Export Finance and Insurance Corporation (EFIC) business breakfast in Melbourne, I got chatting with a prominent figure in the agribusiness sector and Order of Australia recipient. We exchanged cards and he contacted me in a couple of days to have a drink and chat about the Chinese export market.

At the arranged catch up, over a couple of hours he shared important insights like ‘Drinking wine makes me h***ny, ‘When you’re a leader, you have a massive libido’ and ‘When I became (head of a state organisation) my secretary was really young…I chose her because she was a really good organiser and she knew how to keep her mouth shut’.

The next day he emailed me to thank me for the ‘nice chat’ and to say that he’d probably ‘had a bit too much to drink’. I didn’t reply and haven’t heard from him since.

I had the presence of mind to extract myself from a potentially ugly situation but, this far into my professional life, I found this a depressing reminder that predatory behaviour lives on in a business environment that fosters it.

Being an articulate, ambitious and ardent woman desiring to rise in the professional world means having to find ways around the repressive coercion of the old guard gatekeepers of leadership who exert a powerful malignant force against one’s rightful desire to rise and flourish.

What would I say to Madison if I could go back and pick up the conversation where we left off?

I’d say: ‘Go out and seek a small job (unless you have already), so you build your people and business skills and resiliance outside the protective bubble of school and home.

I’d say: ‘Share your thoughts with your teachers. Help raise your school’s awareness of life lessons and learnings that students like you crave and that aren’t always fulfilled by ‘inspirational alumni’ talks.

I’d say: ‘Go out and volunteer. Share your journey with those who struggle – give and show solidarity.’

I’d say: ‘Strategise for your career so you’re prepared and know how to go in to bat for yourself when it comes to pay rises, career opportunities and ‘taking your seat at the table”‘.

And I’d encourage her to keep up the conversation with peers, mentors and leaders. Hold people to account, Madison. Gather support around you and make your voice heard so you can help chip away at that intractable discrimination that blights our workforce and society.

That way, I hope you and other young women and men build preparedness and skill into your DNA. And maybe one day at some school you’ll stand and say: ‘It’s tough out there. I lived it, I struggled – I still struggle – but here’s how I found my way’.