We risk reinforcing bias when we reach for the same old pool of cultural narratives in seeking to raise awareness and support change.

The other day a LinkedIn connection who has unconscious bias training in her repertoire posted a trailer for a documentary, The Mask you Live In, on a culture of toxic hypermasculinity in the United States and its harmful effects.

‘Sounds interesting,’ I thought, and clicked on the link. If it’s anything like the taster, the documentary is powerful and disturbing. Since its 2004 release it’s been made available for special screenings across the United States and has featured in debates and forums (Maybe, if you’re in the United States, you’ve seen it). A necessary testament and mechanism for change in the workplace and in society.

But as I watched, I actually started feeling unreasonably hostile to the clip.

My colleague had referenced this clip as a discussion point that would have broad relevance. Indeed. But I started thinking, ‘How do I relate this landscape to myself and my ‘people’? It’s just one of many realities I should be aware of but I can’t shoehorn this reality into mine. So what am I meant to make of this taster?

With this documentary (what I glimpsed) that sought to draw attention to a profound and corrosive issue, I felt that even here, the agenda was underpinned by unconscious cultural bias.

The Mask You Live In – a US documentary that follows young boys as they struggle to stay true to themselves within a narrow cultural value that values hypermasculinity

What we had, buzzed across global social media, was an important documentary that nonetheless placed the United States at the centre of a hegemonic moral universe of hypermasculinity, especially in its use of the inclusive ‘we’, ‘ours’, ‘our’.

Even the use of the word ‘America’, used widely in the English-speaking world to refer to the United States, reduces our cultural vision to one country only out of the Americas. Spanish-speaking Latin Americans find this culturally offensive: ‘America’ is a continent, not a country. In recognition of this, the Spanish terms are ‘Estados Unidos’ and ‘Estadounidenses’ for the United States and…well, United Statesers. As far as I know, there isn’t a more specific English word in general use. I have to admit that, having strong Latin American and Spanish cultural connections, ‘American’ sticks in my craw.

And as an Australian, similar to many others from former colonies, I have an instinctive aversion to cultural hegemony or cultural arrogance. This deep cultural reserve plays out widely across Australian business settings through to casual ‘American-bashing’ in day-to-day interactions which can bewilder and hurt people from the United States.

Returning to the trailer – here we had unconscious bias writ large, if unintended. As professional interculturalists, there’s a deep irony and risk when we reach for narratives and resources that reinforce cultural and structural bias and narrow cultural interpretations while all the time seeking to unpack and change unconscious bias. Besides, these days, there’s so much less excuse to. There is literally a world of narratives to find, learn from and share and social media is a magnificent platform to do so.

My second reaction to the clip was confusion. What am I meant to make of hypermasculinity here? Am I to accept this definition, as defined by this video? Without going into ‘hyper cultural relativity’ and without going into definitions and discussions about hypermasculinity, can I gain a more nuanced understanding of it by considering other cultures?

A few years back living and working in El Salvador, my main social circle was mostly made up of young professional, upper middle class (in the Salvadoran sense of ‘middle class’) men. They were insurance brokers, lawyers, engineers, financiers. Their dress code was crisply formal during the week, jeans and surf wear for the weekends. From Thursday night until the wee hours of Sunday they would hit the bars, hard. Weekends usually included beer-laced surfing down to La Libertad on the Pacific coastline. Their group language was loud, jocular and insulting – their behaviours competitive, if on the harmless end of it. They were comfortable in their own skin, men in a man’s world and not afraid to exchange opinions on their appearance, their fashion accessories, their imaginary paunches. They proclaimed gender equality and rights to one’s sexual orientation, but machista Salvadoran culture around them had not caught up and their own behaviours betrayed it.

I would call them on the more benign end of hypermasculine. Yet in their way, these friends were happy, financially secure, enjoyed their lifestyle. Their group culture fit in with El Salvador’s broader group culture profile. No suicidal tendencies, no social exclusion, at least on the conformist surface.

Of course, the downside of Salvadoran hypermasculinity is all too apparent. Extreme behaviours, gang culture, social exclusion, high homicide rates, constant lurking violence, noxious conformity, deep-seated impunity. This was also a narrative I knew and understood, having lived and witnessed it. My awareness stays honed through my Salvadoran friendship networks, social media and the news media. Likewise here in Australia, I know and understand the values, behaviours and codes of hypermasculinity, even if from its edges.

Watching the clip, I longed for a cultural perspective from elsewhere, where the psychology of masculinity emerges from a different cultural reality and plays out with different nuances and results. I felt frustrated, cheated, almost. And I was disappointed that my colleague – a Singapore-based Aussie – hadn’t shared a clip from the Asia-Pacific region or Australia. ‘Can’t you do better than yet another documentary about social breakdown in the United States?’ I thought. Most unfairly, of course. This was just one clip!

So to be proactive about it, my task is to keep stepping out of my own unconscious biases by constantly seeking different cultural spaces and narratives to tap into and absorb. And, by example, encourage others to do the same.

How to do it? How can you be more culturally effective and step outside your own unconscious cultural biases when seeking to understand complex, multi-faceted cultural characteristics? How can you access a more broadly representative scope of material for informing and instructing your culturally diverse audience?

Some ideas:

- With a little effort, you’ll find rich insights from around the world outside the Anglosphere…and learn about different digital and business landscapes too. This morning, in a nice synchronicity, my Costa Rican (actually, Salvadoran mother, Honduran father) friend Victoria posted a biting, lightly deft ad from Latin American agency David lampooning sexism in public health discourse: TetaXTeta. Here, Enrique’s tetas (breasts) play their part in reducing breast cancer.

- If you speak more than one language (even at a basic level), make use of it to broaden the cultural scope of your posts. This will open up a vast richness of cultural and business insights. You get to access the popular stuff people love and they’re great resources too. Facebook and other locally popular social media networks are excellent sources.

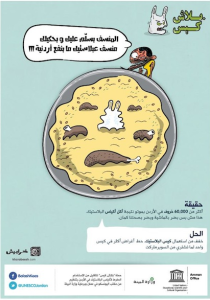

- If you don’t speak the language, don’t be put off. I follow a number of groups whose language I don’t understand. No worries. Google Interpreter…and the visual messages alone are insightful. While looking for a ‘Say no to Plastic Bags’ visual for a blog I was editing on behalf of a client, Dancing Wombat, I stumbled across this great media campaign from Jordan – ‘Balash Kees’, or ‘You Don’t need that plastic bag!’

Balash Kees! No need for a bag! The Jordanian campaign against single-use plastic bags shows a plastic bag in the middle of a platter of mansaf, the traditional Jordanian lamb and rice dish.

I didn’t understand the language but I found some English language information about the campaign, learned about one of Jordan’s cartoonists and got great insights into some of Jordan’s social issues. And now I know what ‘kees’ means!

- Use your social media contacts and friends around the world to ‘share forward’ great material that they post on LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter and other forums. They’ll appreciate your interest and you’ll generate great discussions and insights. Right now I’m having a 140-character dialogue with a Spanish Twitter contact about social mobility and community approaches to youth unemployment. Now and again we break into Spanish.

Also if you’re posting articles or clips, take care about what you’re linking them to:

- If you’re posting to social media like LinkedIn, Facebook or Twitter, ensure that it’s the whole article or the whole feature, not simply a teaser with a paywall behind it, or a preview with no pathway to watch the full presentation. You may end up disappointing or irritating your viewers

- Don’t make sweeping assumptions that your readers have a paid subscription to the source of your post that sits behind a paywall. Individuals and organisations often have a limited budget for subscriptions and you can’t assume that they subscribe to the same publications that you do.

What are approaches that you use to inform and instruct your culturally diverse colleagues and audiences? I’d love to hear your own examples or stories from your own experience that have helped you step outside your own unconscious biases?